UNESCO’s Riel Miller argues that in times like these it makes sense to take a step back and let new ideas about why and how to imagine the future to help us make new and better choices today. We need a new skill set for a different context.

Riel Miller interviewed by Per Koch, Forskningspolitikk

(This is an extended version of an interview published in Forskningspolitikk #1 2018.)

These are times of transformation and upheaval. Many find it hard to meet these changes in any meaningful manner, as existing tools and concepts were built for another time. We still have not grasped what the new one needs.

Riel Miller, who now leads UNESCO’s Futures Literacy activities (often referred to as ‘foresight’), has been looking at different ways of thinking about the future for his entire career, with the Ontario Government, at the OECD and as a private consultant. He has worked with The Research Council of Norway, Innovation Norway and the Technology Council of Norway.

His doctorate is in economics, but his practice has mostly been focused on designing processes in which people think about the future. Gradually this led him to pioneer what he calls Futures Literacy.

Forskningspolitikk met Riel at a café in Paris in December last year.

Could you say a few words about Future Literacy and the discipline of anticipation? What is the point of all this?

I want to be quite clear on this point because I think it is not always easy to keep in mind: Future Literacy is a competence, a capacity. Like many competencies it is a multifaceted thing. It includes technical skills, processing skills, social skills, outcomes, awareness.

The term ‘literacy’ is used exactly because it refers to a capacity. Like reading and writing literacy, Futures Literacy is the ability to create and to understand and to share different reasons and methods for imagining the future.

The starting point is that the future does not actually exist. You have no choice but to use anticipatory systems and processes, to imagine a future. This is the case of conscious human anticipation. So we use our anticipatory systems and processes to create, fabricate, different imaginary futures.

The discipline of anticipation is the field of research and practice that explores the anticipatory processes in the world around us.

So this is not only about predicting the future? In research and innovation policy making you have a whole system of quantitative research, econometrics, and management by objectives that are tools meant to establish some control over the future. What is the relationship between Futures Literacy and that kind of policy making?

In some ways it can be quite disruptive. There is a very important issue here that has to do with diversification of why and how to ‘use-the-future’. Establishing different ways and different reasons for thinking about the future.

If I told you that the only reason to eat is because it makes us have enough calories, you would say ‘well, of course that is true’, but that is really not the only reason we eat. We eat for social reasons and to experience new tastes. Eating and cooking also involve creativity.

Thinking about the future of eating is about more than just survival or predicting how many calories you will consume. Taking this more open perspective on the future invites us to diversify both why and how we imagine the future.

I deploy the somewhat unfamiliar phrase «use-the-future» because it provokes people to consider the role and methods for imagining the later than now.

Just yesterday I was leading a Futures Literacy Laboratory in Tunisia and someone asked me: ‘If the future does not exist, how can you use it?’ I said: ‘Precisely! The future does not exist, but our imagination exists, and we use our imagination, to create futures that we can use to plan, to go to movies, to make appointments, to prepare, and to do many, many things.’

We are so accustomed to ‘using-the-future’; it is so central to what we do, that we just take it for granted. And we do not really reflect on the question, of how and why we do so.

Future Literacy is the skill that enables us to diversify the reasons and methods we deploy when ‘using-the-future’ beyond forecasting, beyond prediction. This does not mean that prediction and forecasting are unessential. Of course, we still want to use prediction when deciding to go meet someone, like you and I today deciding we would meet at this café. We still want to be able to use what happened in the past to think about what may happen in the future.

Efforts to mitigate carbon emissions in order to address climate change is a powerful example of using predicted futures based on extrapolation to make decisions. In this case we have evidence from the past, we have evidence in current indicators, and we think that this means that the climate will change.

But accepting this kind of predictive assumption does not mean that we know what will happen, just that we are willing – for a variety of reasons – to make certain assumptions.

Furthermore, even if we do make some assumptions that describe the imaginary future, it does not mean that many other aspects of the world around us should be given similar deterministic treatment. Assuming that the sun will rise, a mega-trend if there ever was one, does not mean that we need to make the same kind of deterministic assumptions when imagining the future of complex emergent human societies.

We can ‘use-the-future’ to do more than predict or search for assumptions that give us the illusion of certainty. Indeed, we can use it in a way that is counter-intuitive, at odds with today’s common-sense. This is one of the most difficult aspects of Futures Literacy: It is possible to ‘use-the-future’ not for the future.

To put it in other terms, we can change why and how we imagine the future by moving away from the dominant approach of likely/unlikely and desirable/undesirable futures. Instead we can ‘use-the-future’ to expand our perception of the present by liberating our imaginations from the constraints of likely or desired futures.

We can open ourselves up to imagining futures that are wild, strange, odd, confused and nevertheless reveal aspects of the present, that would not be noticeable or meaningful if we simply restrained our thinking.

I can give you an example: If my main concern about the future is that people should have jobs, and I believe education is the way to make sure people will get jobs in the future. Then the futures my imagination invents are going to be about education and jobs.

In other words, I will have projected the organizational forms that dominated the past into the future. As a result, my preoccupations in the present, what I perceive and what gets privileged by my paying attention to it, are the familiar ways of doing things.

Education reform to meet the needs of predicted future jobs will be my main interest, even though efforts at this kind of supply-demand forecasting and planning have repeatedly failed in the past and all around the world. Because, as it turns out, one of the fundamental characteristics of ‘market economies’ is the complex emergence through cycles of birth and death of companies, sectors, jobs, etc. It is not predictable.

Or, if you want to extend the thought experiment, imagine we are in 1750, before the big changes of the industrial revolution, and we were trying to describe the future of peasants in 1800. Would you be thinking about all the different ways to preserve that past in the future? Would you notice what Adam Smith was noticing?

This is the challenge of Futures Literacy, to take off the blinders of projection and improvement and instead ‘use-the-future’ to sense and make-sense of emergent novelty – phenomena that do not yet have a name?

How do you do this more concretely? You are asking people to think outside the box, maybe even – to a certain extent – to let go of their own prejudices. But how do you do that? Is there some kind of methodology people can use?

That challenge is something I have worked on for some thirty years now. When I ran my first futures exercise in 1988, called Vision 2000 on the future of the Ontario Community Colleges I noticed that it was actually very difficult for people to think explicitly about the future. Like asking someone who doesn’t know how to paint to imitate a grand master.

For the most part few people actually spend time cultivating their ability to imagine the future. On the one hand because for most everyday things we’ve learned how early on and take it for granted. On the other hand, because it is hard and in many cultures it is a task left to experts.

Of course, oracles, astrologers and forecasters think about the future all the time. So if you get a group of forecasters together, or a group of astrologers together, and ask them about the future, well, they have been talking about it all along.

But if you get teachers or policy makers, they will often say: ‘Well the future is later’. And I am thinking about ‘later’, but it is pretty vague, and somewhat intimidating.

They might say: ‘I am not a science fiction writer! How can I be creative about the future! I do not have any of those skills. I have never done that before!’ So people feel inadequate.

It is tempting to ask people what they think about the future of biotech, nanotech, innovation, fishing, oil, energy – it does not matter – but without any technique or practice the results are generally highly repetitive and backward looking.

So one of the things that occurred to me as I experienced this problem was that we need to create a learning environment. We need a way to get people to practice ‘using-the-future’, to begin to scaffold-up their imaginations. People have to know the alphabet before they can parse words, and they need to be able to read words before they are able to read sentences. Then they can start to identify different kinds of writing, like science fiction or detective novels or poetry or nonfiction or whatever.

This led me to start experimenting with learning-by-doing activities aimed at developing people’s ability to imagine the future. This kind of action-learning in a very tangible and traditional approach. And I started to see people build up their awareness of what it takes to imagine the future.

Only, at the same time, I started to notice that the assumptions people were using – what I now call anticipatory assumptions – were often restricted into certain categories. Fell into the same patterns. That was when it started to dawn on me that we didn’t know how to think about thinking about the future.

Which is what led, eventually to developing a full theoretical framework for Futures Literacy and a practical approach to grasping the diversity of reasons and techniques for imagining the future in different contexts. This practical approach I call Futures Literacy Laboratories.

And although Futures Literacy Laboratories are certainly not the only way to explore and learn to master the ‘use-of-the-future’ it turns out it is an effective and efficient approach.

You are using this methodology right now, within UNESCO and with members of UNESCO. Can you give a few examples of how this is done?

Day before yesterday I was in Tunisia, and we ran a futures literacy laboratory on the future of women entrepreneurs in Tunisia. We conducted the workshop with 40 Tunisian policy makers, women entrepreneurs, men entrepreneurs, and we discussed the future of women’s entrepreneurship.

How did we do it? We did it precisely through learning by doing. In a Futures Literacy Lab people are invited to make tacit knowledge explicit through conversations that create shared understanding. These processes harness the collective intelligence of a group by taking them through a universal and very conventional learning process.

In phase one participants talk about what they predict the future will be like. This is the probable future and just about everyone bet they are willing to make. In Tunisia they said: ‘Well, I think in Tunisia women entrepreneurs are going to be facing some problems in 2038 (which was the year in the future that we chose), around the regulatory system, the laws.’ That was a prediction.

Then we discussed what they hoped would happen. They hoped that women entrepreneurs would have no obstacles in the system around them – the banks, but also, for instance, partners. As quite a few of the women entrepreneurs explained that initially many of the men were skeptical about a woman being an entrepreneur, and they hoped that in 2038 those obstacles would be overcome.

After the group discussed their hopes and expectations, they realize that they haven’t been thinking very much about the future, and that they can think about the future in more detailed and creative ways.

Here they are still in a fairly conventional approach. They think of the future as a place they want to go to. But how do we think about it in a more open way?

And this is where we go to phase two of the learning curve, which is a little bit more difficult. It is not tacit to explicit. It is a reframing. In Tunisia we got the participants to reframe women’s entrepreneurship in Tunisia by thinking about a world in which they were able to do what they wanted.

How did that work? How did they communicate and connect? We used a visual metaphor, one that I have used before. It’s what in English we call a ‘murmuration’. A murmuration is a flock of birds, generally starlings, that fly together in swirling patterns that defy rigid patterns of centre-periphery or up-down or solid blocks versus fragments.

To reframe the participants need to let go of existing and familiar patterns by starting to play, imagine how things happen in daily life in a strange world, with new organizational forms, habits, relationships.

This is the steep part of the learning curve, the participants work in small groups for an hour and a half, imagining what life is like for women entreprenurs in this diversified, transparent, low cost, high confidence, and highly fluid world. Then the break out groups report back to plenary to share their descriptions of the murmuration society – or as I often call it – the learning intensive society.

Once we’ve collected their attempts to describe this disruptive, odd situation, the ‘lab’ moves to the third phase in which the groups contrast the reframed futures of phase two with the likely and desirable futures of phase one. They begin to see how their initial anticipatory assumptions framed their imaginations and how they can play with the assumptions to push their imaginations in new, unexpected directions.

Finally, this creates the conditions, including the willingness to be creative and change assumptions, needed to ask new questions. In the case of Tunisian women entrepreneurs there were new questions about the role of peer to peer payment systems and verification over the internet.

They started to question the role and nature of current institutions and habits. They saw today’s possibilities in new ways and could begin imagining how current systems for establishing trust and meaningful communications might be hiding other options or obstructing certain changes. In the end they said: «We have some new things we can think about that we weren’t thinking about before. We are starting to see how we can ‘use-the-future’ to see things differently in the present.

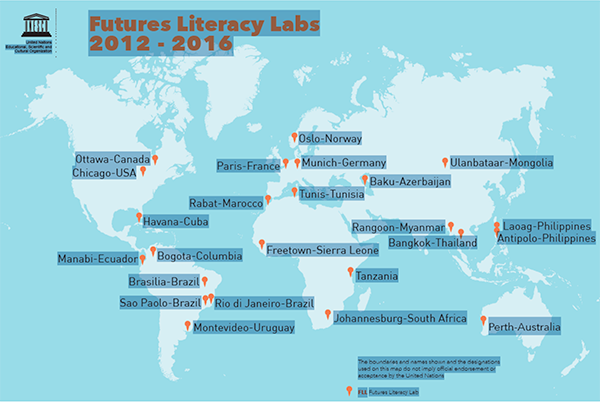

Over the last five years UNESCO has run more than 36 such Futures Literacy Labs, on a vast range of subjects, with a broad range of different kinds of participants, spanning every continent.

UNESCO has been engaged in an innovation cycle – doing proof of concept work to show that Futures Literacy can be identified and developed all around the world and on all different levels. In Uruguay we worked with the Cabinet Office. In South Africa we worked with universities. In Thailand, where we brought together people run informal education across the Asia Pacific. In Paris we engaged 500 young people in a lab that involved over 80 break-out groups and was facilitated by their peers who had been trained the day before.

Now Futures Literacy Labs are moving from the proof of concept phase of the innovation cycle to the prototyping phase. We’re looking to set out the design principles that will allow us to scale-up Futures Literacy, to seed it around the world, bottom-up.

This is more of a democratic process, rather than a technocratic process?

I hope so. I compare it to reading and writing, the skill of literacy that was such a crucial part of the development of industrial urban society. Think about it, when the industrial era took off, there was huge problem of illiterate peasants moving into the city to take jobs in factories.

The problems were legion. They could not read the advertisements needed to find a job or navigate city streets using street signs or decipher the instructions on the factory wall to help them avoid accidents. It was even odd for people bred to distrust a stranger from outside the village to begin collaborating with someone they had never met.

Today it may seem obvious, with hindsight, that the introduction of universal compulsory schooling played a crucial in enabling the capabilities needed to make the transition to industrial life. Schooling changed the conditions of change.

This idea of changing the conditions of change is not that strange, we all understand that a community where everyone has a smartphone can organize and behave in ways that are different from a community without such devices.

If we think about Futures Literacy as the way people ‘use-the-future’. And if we see that knowing how to ‘use-the-future’ differently means we can change what we see and do in the present. Enabling us to take a different approach to uncertainty, reconciling our idea of human agency with the constant novelty of our unescapably complex emerging reality.

Then the conditions of change change. Uncertainty changes from being an enemy of planning to the friend of improvisation, freedom and evolution’s creativity. We begin to feel more at home with diversity, and more at ease in a world where uncertainty is the basis of our freedom. There would be no freedom if we lived in a deterministic universe.

This could be understood to be in conflict with the trends we see right now. We are living in interesting times. We are having – at least in some countries – increased tribalization, and people retreat into dogmas and God given truths. How do you see Future Literacy within this context of increased conflict?

Oddly I am reassured by the observation that Futures Literacy and collective intelligence knowledge creation labs are emerging from the evolutionary creativity of the world around us today. Humanity is bumping up against the dysfunctioning and limitations of world views that cannot reconcile our ability to think and act with the amazing novelty of a creative universe.

Old systems, organisations, habits, and even words are in decline. Of course this sparks nostalgia and an inevitably doomed scramble to preserve yesterday’s certainties. In a transition, which is what we seem to be going through, it is not surprising to confront ‘poverty of the imagination’. A highly dangerous condition that makes us more prone to the horror of winner-take-all and zero-sum thinking.

Humanity needs Futures Literacy now because we have to renew our sources of hope. Old systems are dying, and new systems are not yet fully born. No wonder we need to become better equipped at appreciating processes of non-deterministic complex emergence.

The dissonances of our time – the protectionism, the fear, the tribalism – these are all reactions that relate to the inadequacy of our existing frameworks, institutions, and conceptions of how to find meaning in our lives. At the moment we don’t have the capacity to exercise the freedom that is inherent to our universe.

And one of the real, significant, painful and destructive aspects is what I would see as the real incongruity between the idea of human agency – that we can determine the future, or «colonize» the future and listen to people who tell us they will impose their idea of the future on the future – all of that is absolutely setting us up for disappointment, for failure, for a sense of disillusionment, and betrayal. This is obstructing a more open approach to the future.

In the context of disillusionment and betrayal, we react in ways that are based on our ability to understand. This is again about the peasant who comes to the city and says: ‘How terrifying I cannot read the signs on the streets to even find out where my family lives. I cannot get into the metro and I do not understand why those bells and whistles are blowing – is it because the boss wants me to show up for work on time.’

And they get scared, and they get angry. And they get defensive and they say that ‘I want to go back to the things I understand.’

Futures literacy is necessary precondition for us to begin to find hope again, and to find meaning in a universe which we cannot turn into a deterministic one. It is just the way it is. We have to move from away from the arragoant view of the future that casts humans in the role of gods who are able to dominate the future. If we begin to adopt a more humble perspective we can begin to gain confidence in our ability to turn uncertainty from being an enemy into being an asset.

We can become much better at sensing and making-sense of the fantastic experimentation that takes place all around us all the time. That is not something we are very good at yet, but I think the development of Futures Literacy is a symptom that we are trying to get better at it.

This means that futures literacy could also be part of what this magazine is all about, research and innovation policy, learning policy, education policy. In this context there are certain trends, drivers, possibilities. What are the ones policy makers should take into consideration right now?

I have spent all of my professional life as an advisor to decision-makers, particularly in government. And I have always asked myself, am I trying to improve existing institutions, current ways of expressing and organizing our collective life? Or is there another way of looking at society? Our collectivity that gives status to the policy of everyday actions, by people who are never monads but always relationally expressive and performative. Right now I am convinced it is both.

You and I both understand the importance of research meant to support policy makers exercising power within the existing institutions and systems for organizing power. We both worked with the OECD, it is an institution that is dedicated to figuring out how the people working in one particular part of our collective existence can do a better job.

This is a very valuable thing to think about, but if you can’t get outside the boundaries of improving existing systems you can’t really pose strategic choices – you can only consider tactical options within one strategic framework.

For many reasons this preservationist or backward-looking point-of-view no longer seems tenable. Today we need to be able to produce strategic distance. We need to be able to step back from what we are doing. We need to be able to ask new questions, not just solve familiar problems.

Personally, I don’t think this is a bad thing, even if it is unsettling or disturbing. Because it might mean that there are new opportunities arising. The overall composition of what is collective action, the presence and role of the nation state may be shifting. A whole new kind of plant may be emerging in the forest, beginning to displace and eclipse the old dominant types. We live in a complex evolving universe.

Getting better at generating strategic distance could allow us to let go of the destructive, non-evolving aspects of the desire for immortality – of lasting forever. A capacity-based change in the conditions of change might make us better able to not only encourage experiments but understand the massive creativity of the world around us. We might be less prone to stomping on novelty, seeing it as a danger because we don’t understand it or feel threatened.

From a research and policy perspective, enhancing our capacity to be open to strategic difference is important, because I think it has very tangible implications for policies meant to nurture innovation. We can get better at allowing emergence, putting confidence in spontenaity and improvisation. Let go of the stress and obsessive efforts related to patching up old and dying systems.

Perhaps being more futures literate would enhance both our appreciation and our ability to generate the diversity that is simultaneously an expression and result of innovation. Getting better at seeing our boxes and continuously stepping inside and outside the every moving boxes, could assist those who try to set policy for the existing power structures to find entirely new ways of playing a role.

What if policy makes were to say: ‘One of the big challenges of me as a provider of public goods, is to spend time thinking about things that I have not made, things that nobody can see, because the way we currently look at the world, obscures and hides so many things. Let us find ways to stand back, to search and invent, using some new tools that help us to sense and make-sense of emergent, unnamed, novelty.’

Policy makers and policy research could focus more on finding strategic distance and dedicate more time and effort to novelty. True, this requires a certain degree of modesty, which is not always easy from the point of view of the state, but it will have a huge public benefit, because they are paid by the community to do that sort of thing – obviously in collaboration with society, enterprises and schools, parents and citizens and the world as a whole.

All of this is rooted in the idea that openness, networking, and diversification are enabled. The energy for creativity and development come from openness. Closed systems die.

Your book will be published in April. What is it about and how do you want people to use it?

The book has been a labor of love. I’ve been working on it for a long time. Working with many brilliant and generous people, yourself included. The book is a reflection of the theory of practice of a number of emerging fields.

The title tells part of the story. Transforming the Future: Anticipation in the 21st Century is meant to suggest that by gaining a better understanding of anticipation, of why and how we thing about the future, we will change the future.

But like all work at the frontier of what is happening it is a work in progress. The terminology, the methodology, the implications – are open. The book does not claim to close the conversation or to definitively define the conversation, but to unleash our seeing and doing.

Still, I’m quite aware that in order to launch a conversation you need to have a sufficient vocabulary, and frameworks for understanding, in common. The book tries to define futures literacy as a capacity.

It contains a theoretical framework, which defines what futures literacy is about, and it provides case studies – that I think provide proof-of-concept type evidence, from a scientific perspective – that show that the categories and theories of Futures Literacy are needed, and that they can be found in the world around us.

The book is rather technical because it aims propose elements of a shared vocabulary for ongoing research and practice of Futures Literacy around the world. We are now moving into the prototyping phase. The time for conducting experiments that demonstrate key propositions in a wide variety of situations.

I am very pleased that one of the main locations for advancing Futures Literacy will be in Africa. The OCP Foundation of Morocco has given UNESCO funding to run the Imagining Africa’s Futures research project. We will be testing prototype Futures Literacy Labs on the ground all across Africa. Similar testing of the design principles and theoretical frameworks presented in the book will take place in other parts of the world.

There are already three new UNESCO Chairs at universities in Finland, Italy and Malaysia. Some ten more are in the pipeline. The development of Futures Literacy is just getting started.

Follow Riel Miller over at twitter: @RielM

Transforming the Future (Open Access): Anticipation in the 21st Century (Hardback) – Routledge

Hovedfoto: Riel Miller at Le Fumoir by the Louvre, Paris. (Photo: P Koch.)