Dorothy Sutherland Olsen and Anne Inga Hilsen take a look at the role of informal and tacit knowledge in learning and innovation. A study of older employees has led to some interesting new insight.

Dorothy Sutherland Olsen, forsker 1, NIFU and Anne Inga Hilsen, forsker FAFO og førsteamanuensis Universitetet i Sørøst-Norge.

Often when we think of the kind of competence needed for good research or for innovation, we think about formal competence. We think about the kind of education researchers or innovators should have or we think about other things which indicate more recent competence, such as the number of publications a researcher has or maybe the number of patents innovators have.

Informal knowledge

These are all valuable and useful ways of assessing competence and ultimately improving the probability of high- quality research and successful innovations. However, for the right competence to be turned into high-quality results, we need a few other things. One of the things we need is informal knowledge.

Informal knowledge is not new, indeed some of the earlier innovation research highlights the importance of tacit knowledge, learning by doing and practice-based knowledge, but since this kind of knowledge is not registered or logged anywhere, we need to be continually reminded of its

importance.

The competence of older employees

We were recently reminded of this in a project about workers over 50 years of age. This was not a project about researchers or innovators, but it provides some interesting examples of informal knowledge and its importance in the workplace. We were studying the competence of older employees.

Most statistics on adult education and training suggest that there is a huge drop in the numbers participating in formal education and other courses after the age of 50. This has led to the assumption that older employees are not able or not interested in developing new competence.

Many of the employees we interviewed said they didn’t know anything; they just did their job. Some were embarrassed to say that they had not been on any courses recently, while others proudly proclaimed that they deliberately avoided attending courses which were «a waste of time».

However, as we gathered more and more data, it became obvious that these employees could do things which their younger colleagues could not and without these abilities, knowledge and understanding, work in these organisations ould not have been carried out in such a smooth and efficient way.

Assessing risk

Some examples of the kind of knowledge became evident when employees told us about how they assessed the risk of new projects. One project manager said he knows that the proposal is like an iceberg, and he knows that there will always be unforeseen problems. He knows what questions to ask to reduce the risk and he told us how he added extra amounts in the budget to be used when the real challenges of the project became evident. He did not break any rules, but his budgeting practice did seem a bit untraditional.

In another example a nurse, who also said she just knew what all nurses know, explained how she was able to calm down patients by telling them about previous situations. She was able to balance between reassuring the patient while still providing factual information and not presenting an overly positive view of the situation.

Although this nurse thought she just knew «what all nurses know», her younger colleagues were not able to deal with patients in the same way. When discussing with several nurses, they pointed out that this calming and reassuring way of dealing with patients was really quite important to the smooth functioning of the hospital and reduced the risk of panic and delays.

The advantage of a diverse work experience

Many of these older employees had several different jobs during their careers. Most of them saw this as an advantage. An example of the benefits was a government employee who had worked in private sector and in a variety of positions, had worked with lawyers, architects, farmers etc.

She found that when she was communicating complex information to others, that it was automatic for her to adjust. She changed the way she spoke or wrote, the terminology, the details and the examples or sketches she used to aid understanding. Her younger boss was aware of her abilities and often asked her to communicate the most difficult or contentious issues.

Auditing

One of the groups we studied was responsible for travelling round to multiple organisations and auditing working routines. Their auditing tasks were highly regulated and required detailed reporting, however even in this situation we found that older and younger employees were doing this differently.

Before they got past the reception, the older employees had already decided whether this organisation needed some extra attention or not. They had trouble explaining this to younger employees, but some said it was small details like how tidy the place was, how quickly people answered questions and provided information. They said, however, that one must experience this, many times, before one can develop this ability. They maintained that this initial assessment was almost always right and improved the quality of their results.

Intuition

These examples may seem like little things which are not very important. Some people have even said to us «this is just natural, maybe just intuition». This comment just strengthens our suggestion that this kind of informal knowledge is common among older employees, so common that it is just viewed as natural.

We have confronted management with some of the findings and they have confirmed that although they were not aware of how older employees were contributing, they could see that their organisations would not function as well without people who could do these things. Maybe this kind of informal knowledge is what oils the works and maybe it is even more important than we realise in our continuous race for efficiency.

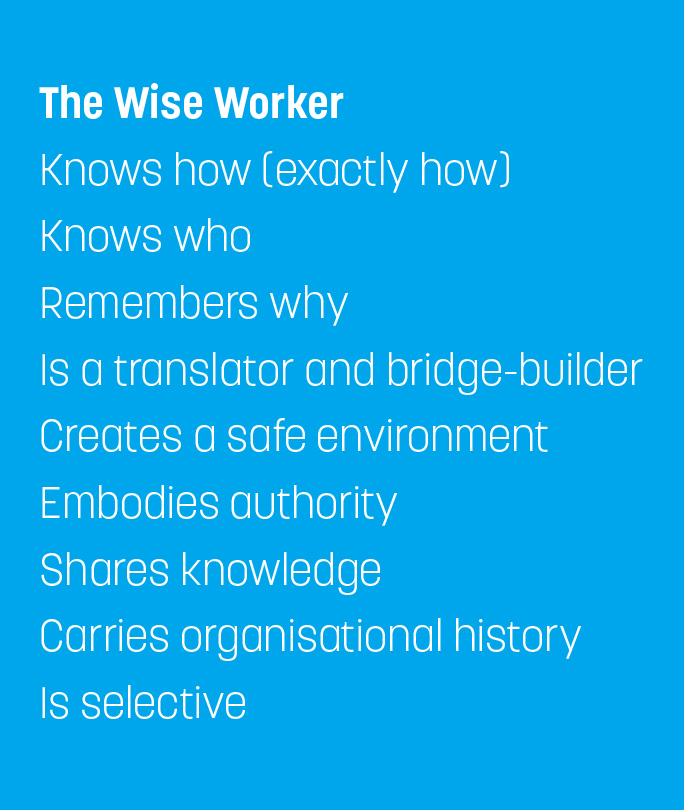

We have gathered our findings together to develop a concept of the wise worker (see text box below).

We hope that managers might try to view older workers as a resource rather than a burden. We also wonder if it might be useful to look more closely at the small actions that keep the wheels turning in other age groups and other fields, like research and innovation.

Examples taken from the book by Olsen and Hilsen: The Importance and Value of Older Employees: Wise Workers in the Workplace. Palgrave 2021. and the Silver Lining project

Photo: Dean Mitchell