Since Roosevelt’s era, U.S. science, technology, and innovation (STI) policy has balanced continuity with adaptation, shaped by both political dynamics and public trust.

Mark Knell, Research Professor, NIFU

Institutions such as NASA (the National Aeronautics and Space Administration) and DARPA (the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency) continue to address evolving challenges such as climate change and healthcare innovation.

However, partisan divides persist, with Democrats often championing scientific consensus, while Republicans question it, particularly in areas like climate science.

Miller et al. (2024) underscores enduring public trust in STI policy despite these political tensions, though trust varies significantly across party lines. As the U.S. nears another election, examining the trajectory of STI policy is more crucial than ever.

Foundations of Modern STI Policy

Modern U.S. STI policy took shape in the 1940s under the presidents Franklin D. Roosevelt (Democrat, 1933–1945) and Harry S. Truman (D, 1945–1953).

Roosevelt’s administration mobilized scientists to support the war effort and to fuel postwar economic growth. Vannevar Bush’s seminal 1945 report, Science: The Endless Frontier, advocated for federal investment in scientific research, shaping the nation’s scientific agenda.

A major turning point came with the 1957 launch of Sputnik by the Soviet Union. In response, President Dwight D. Eisenhower (Republican, 1953–1961) established NASA, ARPA (now DARPA), and the President’s Science Advisory Committee (PSAC), signaling a new era of space exploration and defense technology in the context of the Cold War competition.

Key Institutional Developments

In 1961, President John F. Kennedy (D, 1961– 1963) institutionalized STI policy by founding the White House Office of Science and Technology (OST), integrating scientific expertise into national decision-making.

Under Kennedy’s leadership, initiatives such as NASA’s Apollo program led to significant achievements, including the moon landing, and the set up of a framework for long-term scientific research.

President Lyndon B. Johnson (D, 1963– 1969) expanded these priorities, increasing funding for National Institutes of Health (NIH) to support Great Society programs and focusing on environmental protection, while continuing the space race. This era solidified a strong Democratic commitment to scientific advancement.

Contrasting Approaches

Richard Nixon’s presidency (R, 1969–1974) marked a shift. Distrusting the scientific community, Nixon dismantled PSAC and cut funding for non-defense research, reflecting Republican skepticism towards science. Yet, Nixon advanced major environmental legislation, including the Clean Air Act and the creation of the EPA (Environmental Protection Agency).

In 1976, Gerald Ford (R, 1974–1977) created the OSTP (Office of Science and Technology Policy) to fill the gap left by the dismantling of PSAC, prioritizing energy research and supporting NASA, DARPA, and the NIH (bio-medical and health). As part of its responsibilities, the OSTP advised the President on scientific, engineering, and technological issues.

Jimmy Carter (D, 1977–1981) later strengthened OSTP, NIH, and NSF (National Science Foundation), focusing on energy, environment, and innovation.

Throughout the Reagan, Bush I, Clinton, and Bush II administrations, the OSTP, NSF, NIH, and DARPA remained central to STI policy, though shifting political priorities often impeded progress.

Ronald Reagan (R, 1981–1989) reduced federal involvement in non-defense research, favoring private-sector innovation. George H. W. Bush (Bush I, R, 1989–1993) promoted climate science and the early internet but faced resistance from within his party.

Bill Clinton’s (D, 1993–2001) policies spurred the 1990s tech boom, focusing on bio-technology, the internet, and clean energy, while George W. Bush (Bush II, R, 2001– 2009) prioritized national security and biodefense, expanding DARPA and NASA funding.

Recent Developments The Obama administration (Barack Obama, D, 2009–2017) prioritized clean energy, healthcare innovation, STEM education (Science, technology, engineering, and mathematic), and workforce development. Obama launched ARPA-E to drive energy technology innovation and the Precision Medicine Initiative to tackle health challenges. His science-forward approach sharply contrasted with Republican narratives.

Donald Trump (R, 2017–2021) deprioritized science in policymaking, leaving the OSTP director role vacant for over two years. Critics condemned his administration for mishandling the COVID-19 pandemic and dismissing climate science. However, investments in AI and quantum computing increased, though broader STI policy lagged behind.

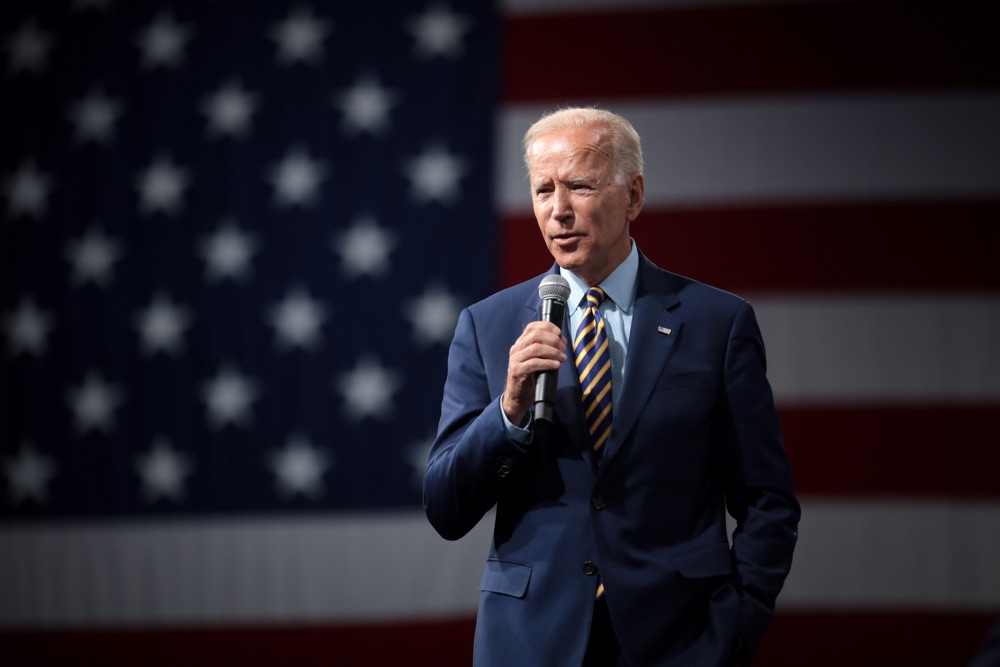

Joe Biden (D, 2021–2025) reversed many of Trump’s policies, elevating the OSTP director to a Cabinet-level position, reinforcing science in decision-making. He expanded the National Science Foundation (NSF) through the CHIPS Act to reshore semiconductor production, strengthened NIH’s focus on pandemic preparedness, cancer research, and biotechnology, regulated monopolistic practices in digital industries, and emphasized clean energy and environmental initiatives.

Conclusion and Future Outlook

Public trust in science plays a crucial role in shaping the effectiveness and future of U.S. science, technology and innovation policy. Miller’s 2024 study shows that overall trust in scientific institutions remains strong despite political polarization, with growing Republican skepticism — especially toward climate science — since Nixon. This erosion of trust, exacerbated by political dynamics, highlights the need to preserve the independence and credibility of scientific institutions.

A second Trump administration, guided by Project 2025, would restructure federal agencies, prioritize energy independence, reduce environmental regulations, and appoint politically aligned scientific positions. While this approach might advance technologies like AI and quantum computing, it risks sacrificing long-term scientific integrity for short-term gains.

A potential Kamala Harris administration would emphasize equitable STEM education, expanding scientific literacy, and rebuilding public trust across political divides. Highlighting tangible benefits — such as healthcare innovation and climate solutions — could reduce partisan skepticism and strengthen support for science. This would bolster U.S. leadership in AI, quantum computing, and sustainable technologies, enhancing global competitiveness.

As Miller’s research shows, sustaining public trust is essential for the long-term success of U.S. STI policy. Whether future policies follow a progressive path or shift toward conservative short-term goals will depend on supporting this trust, particularly in addressing critical issues like climate change and pandemic preparedness.

Litterature

Chris Mooney (2005), The Republican War on Science, Basic Books

Jon D. Miller, et al. (2024), Citizen attitudes toward science and technology, 1957-2020: measurement, stability, and the Trump challenge, Science and Public Policy.

Top photo: alexls/Getty