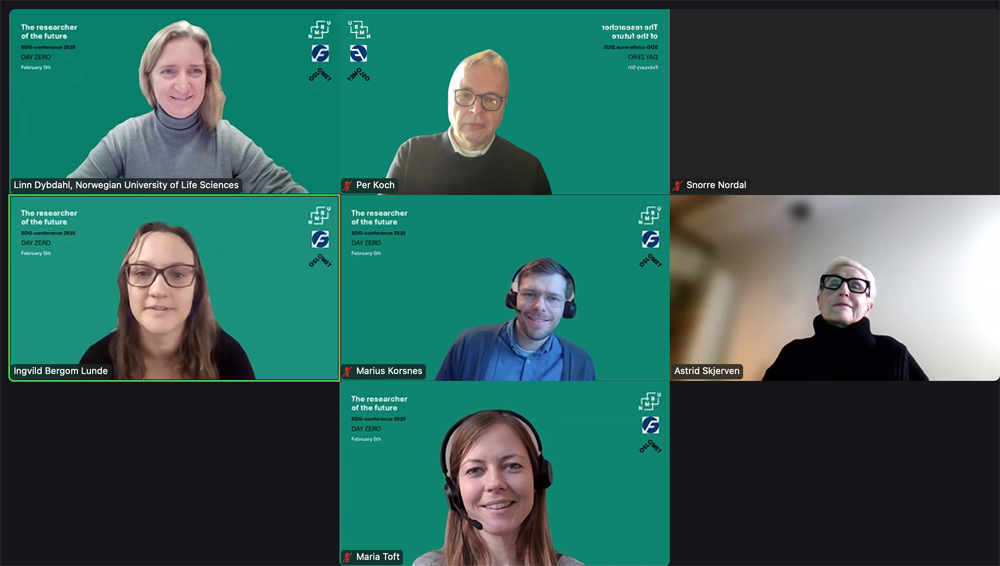

NMBU, OsloMet and Forskningspolitikk invited to an online seminar on the researcher of the future today. The seminar was part of DAY ZERO of the Bergen SDG-conference 2025. Here we publish one of the introductions. Forskningspolitikk will follow up with articles from some of the other participants.

On discussing the researcher of the future

Introduction by Per Koch, editor of Forskningspolitikk

I am a UNESCO Chair in Futures Literacy, a scientific tradition looking at how people use the future when making decisions.

What we have found is that for the most part we do not have a conscious idea about how we use the future. We are not future literate, to put it that way. Instead, we create images of the future based on existing mental maps, concepts, words, narratives and institutional structures.

There is also a tendency for us to imagine a future where our own tribe comes better out. If university researchers are to imagine a better future, it will normally be one with more money for basic research.

In other words: We use ideas and methods developed to solve the problems of yesterday to solve the problems of tomorrow.

Because of this future scenarios often become projections of the present – of a slightly better future. There will still be cars, but they will be flying. It is much harder to imagine a future without cars. It is so much harder to imagine a future where what we now take for granted is no longer there.

Crises and more crises

I read this morning that Trump now wants the US to annex the Gaza Strip. None of us has included that policy proposal in our future scenarios. Yet, here we are. We have to prepare for the unthinkable.

It seems to me that it has become much harder to believe in a better future based on technological progress and an open democracy.

We are facing an increasing number of crises: Climate change, the rice of fascism, unfettered AI, microplastic in our brains, war in Europe and the Middle East and so on and so forth. The traditional political system and its institutions have not been able to deliver the solutions we need.

Indeed, fascists like Putin and Trump are now actively destroying the institutions we have used for this purpose, preaching the gospel of self-interest, imperialism and brute force instead.

So if we are to discuss the future role of the researcher we need to aim higher than tweaking the system we have today.

Science and society

There is particularly one myth or narrative that I believe must go, and that is the one about scientists standing outside society. There is this belief that scientists are distant observers looking into society, providing people with disinterested and objective facts.

There is no doubt in my mind that the scientific method is superior to most forms of discourse, also when it comes to developing a shared understanding of what is real. The scientific method has self-correcting mechanisms like an ordered discourse, peer review and academic diversity, mechanisms that in the end may correct fundamental misunderstandings and errors.

But this method has not stopped science from being an instrument for abuse and oppression, as in the cases of animal welfare, race, gender equality and LGBTQ lives.

The reason for this is partly that researchers, like all humans, are locked into their own prejudices and the interests of their own tribes. They see what they want to see.

But on the positive side, scientists have also channeled social concerns and desire for justice into their work, contributing to the welfare of people and nature in the process.

My point here is simply that scientists have always been a part of society and that they should be a part of society. But they need to be consciously aware of that role and take responsibility for what they are doing. This also means that they have to be pro-active when it comes to addressing the current crises, including the sustainability goals.

Although we can and should defend the public funding of curiosity-driven basic research, I would say that right now we need research institutions to face the music. We are in deep trouble.

Lock-ins

This also means that we have to questions the way we organize research. Are today’s universities delivering what we need? I would say no. We often leave our prioritization to scientists and students. They are definitely important stakeholders, but so are members of other knowledgeable communities.

Are research institutes and companies delivering the research we need? Sometimes, yes, but they are also locked into the needs of the market or of policy makers trapped in their own prejudices.

Indeed, most of the crises we are facing right now are partly created by science and innovation. That obviously applies to climate change. But this also applies to the rise of fascisms, which has been fueled by the polarization of social media and science based psychological warfare.

So I would ask our panelists to question the role of our institutions. Maybe we need different institutions for learning?

And I would question the role of the researcher. Maybe we need alternative ways of exploring reality and coming up with solutions to the crises, alternatives that include the experience and wisdom of people outside academia.

Main illustration: yogysic